Shipgirl Showcase Special Edition:

So, as most of you readers know, my passion for history is basically the only thing keeping this thread open, much less semi-active; and, well, I'm going to be honest. One of the reason I got into studying naval history in particular was due to my maternal grandfather, who joined the Kreigsmarine shortly before World War II kicked off. He did so partly for the pay, which at the time was considerable, but mostly because the German Navy was full of Imperial Navy and Reichsmarine veterans, which meant that the entire command structure was made up of people that had even less tolerance for the Nazi ideology than most.

This does not absolve the Kreigsmarine from its actions, of course, but I just wanted you to get an idea of where I'm coming from when I point out that, of all the warships in the world, the first one that I

really learned about was the Bismarck.

So, without further ado, a Showcase for the most-famous, and infamous battleship built by Germany.

[Bismarck-class]

Probably the most-infamous warships to ever touch the Atlantic ocean, the Bismarck-class battleships are, on paper, formidable. The third-most-armoured ships in the Western hemisphere, only behind the Scharnhorst class and King George Vs, the Bismarck class was designed from the ground up not as a raider, but as a brawler, intended to get in close to enemy formations in the high seas and nearly nonexistent visibility of the North Sea, which factored in to many of the design decisions that left the last German Battleships being widely considered the pinnacle of World War I-styled designs.

With a top speed of 30 knots making them as fast or faster than any other battleship at the time,with very few exceptions, Eight 15” rifles in four main turrets, a total of 28 secondary and tertiary guns (150mm secondaries and 105mm dual-purpose guns), and a not-inconsiderable number of light AA guns, the Bismarck-class was designed before air power’s dominance came to be known; subsequently, after the loss of Bismarck due, in no small part to the efforts of naval aviation, Tirpitz was loaded with as many light and medium AA guns as was humanly possible.

Of note is that the Bismarck-class were the last battleships constructed with a ‘Turtleback’ Armour scheme, involving sloped internal armour decks to deflect enemy cannonfire away from the machinery spaces and ammunition magazines. While considered obsolete compared to the All or Nothing armour scheme used by virtually every nation after 1922, it was still incredibly capable of keeping the warships combat-capable in the role they had been designed for.

[Bismarck]

Undergoing sea trials in 1940, Bismarck managed to be imposing even at rest.

Undergoing sea trials in 1940, Bismarck managed to be imposing even at rest.

So, here she is. The boogeyman of the entire German navy, the ship that was so infamous that in a week’s span, she went from ready to deploy on her very first mission to being run down by every Royal Navy Asset in the Atlantic that could be spared.

“The British would ultimately deploy six battleships, three battlecruisers, two aircraft carriers, 16 cruisers, 33 destroyers and eight submarines, along with patrol aircraft. It would become the largest naval force assigned to a single operation up to that point in the war.”

Launched on February 14th, 1939, Bismarck’s fitting out and trials were held in the Baltic sea, with her only commander being Ernst Lindemann, a man known for being both the premier large-calibre gun instructor in all of Germany, and also insistent that crew within his hearing only refer to Bismarck as “he”, as, in his words, “No vessel of war this powerful could ever be considered female.”

Naturally the crew ignored Lindemann’s edict, regardless of how much they respected him. During maneuver trials lasting from August of 1940 to March 1941, the warship’s crew discovered a severe flaw in the design; one that would eventually become lethal; due to how closely-set the battleship’s three propeller shafts were in relation to the broad hull, (at 118 feet wide, only the Yamato-class battleships were wider from side-to-side), it was discovered that while it was possible to steer the Bismarck using only propeller output, it was nearly impossible to hold a steady course.

“The Naval High Command (Oberkommando der Marine or OKM), commanded by Admiral Erich Raeder, intended to continue the practice of using heavy ships as surface raiders against Allied merchant traffic in the Atlantic Ocean. The two Scharnhorst-class battleships were based in Brest, France, at the time, having just completed Operation Berlin, a major raid into the Atlantic. Bismarck's sister ship Tirpitz was rapidly approaching completion. Bismarck and Tirpitz were to sortie from the Baltic and rendezvous with the two Scharnhorst-class ships in the Atlantic; the operation was initially scheduled for around 25 April 1941, when a new moon period would make conditions more favourable.

Work on Tirpitz was completed later than anticipated, and she was not commissioned until 25 February; the ship was not ready for combat until late in the year. To further complicate the situation, Gneisenau was torpedoed in Brest and damaged further by bombs when in drydock. Scharnhorst required a boiler overhaul following Operation Berlin; the workers discovered during the overhaul that the boilers were in worse condition than expected. She would also be unavailable for the planned sortie. Attacks by British bombers on supply depots in Kiel delayed repairs to the heavy cruisers Admiral Scheer and Admiral Hipper. The two ships would not be ready for action until July or August. Admiral Günther Lütjens, Flottenchef (Fleet Chief) of the Kriegsmarine, chosen to lead the operation, wished to delay the operation at least until either Scharnhorst or Tirpitz became available, but the OKM decided to proceed with the operation, codenamed Operation Rheinübung, with a force consisting of only Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen.”

In theory, if the planned operation had managed to collect all four modern battleships, backed up with three of the four heavy cruisers available, it would have very likely gone far differently. But, instead, spurred by political pressure and the knowledge of the upcoming Operation Barbarossa, which the Kreigsmarine would have little involvement in, the OKM high command ordered Bismarck’s first mission to be carried out immediately.

And so, on the 20th of May, 1941, Bismarck would set sail on her first, and last combat mission, and into the annals of history.

Within German waters, on the way to their first staging point near Bergen, Norway, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were spotted not only by a dozen planes on patrol from Sweden, but also the seaplane tender/cruiser Gotland, which promptly reported on the movements of “Two large ships, three destroyers, and five escorts” to both Swedish command, and, through back channels, the British Admiralty.

Of course, the Germans tasked their own reconnaissance flights to make sure that the Home Fleet remained in Scapa Flow, which ended up falling for the oldest tricks in the book; it turns out wood and canvas props, at sufficient distance, can look like battleships at anchor.

Upon refuelling and repainting at Bergen, Bismarck and Prinz Eugen detached from their destroyer screen and headed westwards, intending to break out into the open Atlantic just in time to see if they could sup upon the eleven convoys heading to the British isles.

“Admiral John Tovey ordered the battlecruiser HMS Hood, the newly commissioned battleship HMS Prince of Wales, and six destroyers to reinforce the pair of cruisers patrolling the Denmark Strait. The rest of the Home Fleet was placed on high alert in Scapa Flow. Eighteen bombers were dispatched to attack the Germans, but weather over the fjord had worsened and they were unable to find the German warships.”

Charging into the ice and mine-choked Denmark strait at approximately 4 AM on the 23rd, at a ‘Damn the consequences’ speed of 27 knots, fog reducing functional visibility to less than 3,000 metres, and both German ships having warmed up their radar sets (and Eugen having warmed up her hydrophone array), Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were alerted to the presence of HMS Suffolk and HMS Norfolk within the ice-choked waterway at the same time the British ships became aware of the German vessels.

Suffolk in her May 1941 arctic paint, shortly after arriving at Reykjavik, Iceland in preparation for her patrol in the Denmark Strait.

Suffolk in her May 1941 arctic paint, shortly after arriving at Reykjavik, Iceland in preparation for her patrol in the Denmark Strait.

“This was Suffolk, racing on a southwest course to travel along the edge of the fog bank; briefly, the three-stacked silhouette of the cruiser was in sight before she plunged into the mist. There was no time to get a bearing or open fire.

Aboard Suffolk, Able Seamen Newell, in the after starboard lookout, was scanning his sector with binoculars. In these latitudes, the ice and light played tricks, and even the most-experienced sailor could be fooled. Suddenly, a great black shape loomed out of the mist no more than seven miles away. "Ship bearing Green one-four-o" he shouted. Then a second ship appeared, and he shouted the alarm again.

Captain Ellis brought Suffolk hard over and she heeled heavily to starboard as he brought her deep into the fog, while alarm bells rang and sailors rushed to action stations, china and cutlery clattering to the floor in the messdecks.

Once safely in the fog, Suffolk slowed down and waited for Bismarck and Eugen to pass her before taking up a position to the rear, just within radar range.

At thirteen miles, this meant the Bismarck's guns could easily reach her at any time. The cruiser roared along at 30 knots, edging at her top speed, and the vibration was tremendous. It was all she could do to keep up with the big German ships, which had increased speed.

In the plotting room, the Suffolk's piloting officer found it nearly impossible to hold the ruler on the chart due to the way the ship was shaking.

Meanwhile, Norfolk had been alerted and was racing back through the fog to join Suffolk. But her captain had misjudged his relative position and emerged six miles in front of Bismarck, with the great gray leviathan closing fast.

Before Norfolk could escape back into the mist, five salvoes straddled her. One shell bounced off the water and ricocheted off of the Captain's bridge. But only shell splinters landed aboard, and no one was hurt.”

An image of Dorsetshire, Norfolk's identical twin sister, at Scapa Flow, August 1941.

An image of Dorsetshire, Norfolk's identical twin sister, at Scapa Flow, August 1941.

Now being followed just within radar range by two heavy cruisers, secrecy had been lost; More importantly, the concussion from Bismarck’s main guns had cracked the FuMO 23 ‘Seetakt’ Radar mounted forward, essentially blinding the battleship’s non-optical gunnery options and early warning system, which prompted a shuffling of position; Prinz Eugen took the lead in the formation, with Bismarck following; her aft radar still functioned, so she could keep track of the two heavy cruisers that now dogged her.

“At around 22:00, Lütjens ordered Bismarck to make a 180-degree turn in an effort to surprise the two heavy cruisers shadowing him. Although Bismarck was visually obscured in a rain squall, Suffolk's radar quickly detected the manoeuvre, allowing the cruiser to evade. The cruisers remained on station through the night, continually relaying the location and bearing of the German ships. The harsh weather broke on the morning of 24 May, revealing a clear sky. At 05:07, hydrophone operators aboard Prinz Eugen detected a pair of unidentified vessels approaching the German formation at a range of 20 nautical miles (37 km), reporting "Noise of two fast-moving turbine ships at 280° relative bearing!"”

HMS Hood and Prince of Wales had arrived.

The Battle of the Denmark Strait remains one of the most-heavily debated engagements in the battle of the Atlantic, but, the long and short of it is that the Royal Navy, already stretched to the breaking point bottling up the Vichy French Navy, the Marina Militaire, maintaining its holdings in the Indian Ocean and Indonesian archipelago, AND fighting a desperate battle against the hordes of U-boats that swarmed the convoys that were so vital to keep the British isles away from total starvation and collapse, had basically thrown a tired old warhorse long overdue for a refit and a near-literal baby less than three weeks out of the shipyard into the path of the Bismarck and Eugen.

On paper, Hood and Prince of Wales would be more than a match for the two German ships; with a total of eighteen big guns to Bismarck’s eight, the biggest concern for the British commander, Admiral Lancelot Holland, was that a shell fired from extreme range would punch through Hood’s lightly-armoured deck and explode deep in the battlecruiser’s guts; so he plotted an intercept that would minimize the threat of a distant shell, intending to close to brawling range where Hood’s main armour belt would take the worst abuse thrown in her direction.

At 5:52 AM local time, Hood opened fire, followed by Wales. Three minutes later, at 5:55, Captain Lindemann overruled Admiral Lutjens aboard Bismarck and commanded the battleship to open fire. Four minutes later, at 5:59, Hood exploded, killing all but three of her 1,418 crew. (I will go into her unfortunate fate in more detail in her own section, and there are more details on the Denmark Strait in Prinz Eugen's own writeup earlier in the thread.)

Painted by J.C. Schmitz-Westerholt while aboard the Prinz Eugen, the original canvas has remarks from the cruiser's captain written on the back.

Painted by J.C. Schmitz-Westerholt while aboard the Prinz Eugen, the original canvas has remarks from the cruiser's captain written on the back.

Wales didn’t escape unscathed either, taking no less than seven hits from both Bismarck and Prinz Eugen, the newly-constructed battleship forced to retreat as a combination of damage and jams left her with only one operable gun; Even with flooding due to two hits at or below the waterline, however, Wales would link up with Suffolk and Norfolk to pursue the small German Flotilla.

“The British battleship scored a hit on Bismarck with her sixth salvo, but the German ship found her mark with her first salvo. One of the shells struck the bridge on Prince of Wales, though it did not explode and instead exited the other side, killing everyone in the ship's command centre, save Captain John Leach, the ship's commanding officer, and one other. The two German ships continued to fire upon Prince of Wales, causing serious damage. Guns malfunctioned on the recently commissioned British ship, which still had civilian technicians aboard. Despite the technical faults in the main battery, Prince of Wales scored three hits on Bismarck in the engagement.

The first struck her in the forecastle above the waterline but low enough to allow the crashing waves to enter the hull. The second shell struck below the armoured belt and exploded on contact with the torpedo bulkhead, completely flooding a turbo-generator room and partially flooding an adjacent boiler room. The third shell passed through one of the boats carried aboard the ship and then went through the floatplane catapult without exploding.”

The first hit would be more telling than the description states; not only did the 14” shell from Wales punch clean through both sides of Bismarck’s bow, but the addition of some 1,000 tons of water forward contaminated a significant amount of the battleship’s fuel reserves, and, as Bismarck continued to head south at high speed, the holes were torn open further due to inrushing water.

With the Royal navy enraged to a level that would make God of War’s Kratos suggest they take a chill pill, and Bismarck’s trail visible due to the thick streams of oil leaking from the bow hit, it was decided that, in order to let Prinz Eugen carry on the mission, the Battleship would loop back to distract the pursuit force, which had just been reinforced internally by Prince of Wales getting 9 of her guns back into readiness. (The tenth, which had failed on the first salvo the battleship had fired, needed to be replaced entirely.)

“Prinz Eugen was successfully detached at 18:14. Bismarck turned around to face Wake-Walker's formation, forcing Suffolk to turn away at high speed. Prince of Wales fired twelve salvos at Bismarck, which responded with nine salvos, none of which hit. The action diverted British attention and permitted Prinz Eugen to slip away. After Bismarck resumed her previous heading, Wake-Walker's three ships took up station on Bismarck's port side.”

While Bismarck’s damage had slowed her down, she could still maintain speeds of 28 knots, meaning only cruisers and destroyers could outrun her; even the King George V-class battleships could match that speed, not exceed it. Thus, the Admiralty called upon HMS Victorious to see if she was up to the task of slowing Bismarck down.

That night, at 22:00 (10 PM), Victorious launched a squadron of fifteen planes to intercept Bismarck, which was still being shadowed and reported on by Suffolk, Norfolk, and Wales. The aviators, raw rookies to a man, very nearly attacked Suffolk, and the nearby American Coast Guard cutter Modoc in the confusion, alerting Bismarck’s anti-air gunners, which caused all hell to break loose.

“Modoc, acting as a neutral vessel that was rescuing survivors from torpedoed convoy vessels, found herself witness to one of the skirmishes in the Pursuit of the Bismarck. Close to midnight of May 24th, Modoc found herself in the midst of an attack in which eight planes and three warships were involved. Antiaircraft fire from Bismarck whizzed dangerously close to the cutter's port bow. HMS Norfolk was about to take the cutter under fire until HMS Prince of Wales identified her as U.S. Coast Guard. The cutter was luckily undamaged, although they were near the fighting and at times only six miles from Bismarck. The widespread movements of the combatants, 19 vessels if one included destroyers and smaller ships, had distributed danger over a wide area.

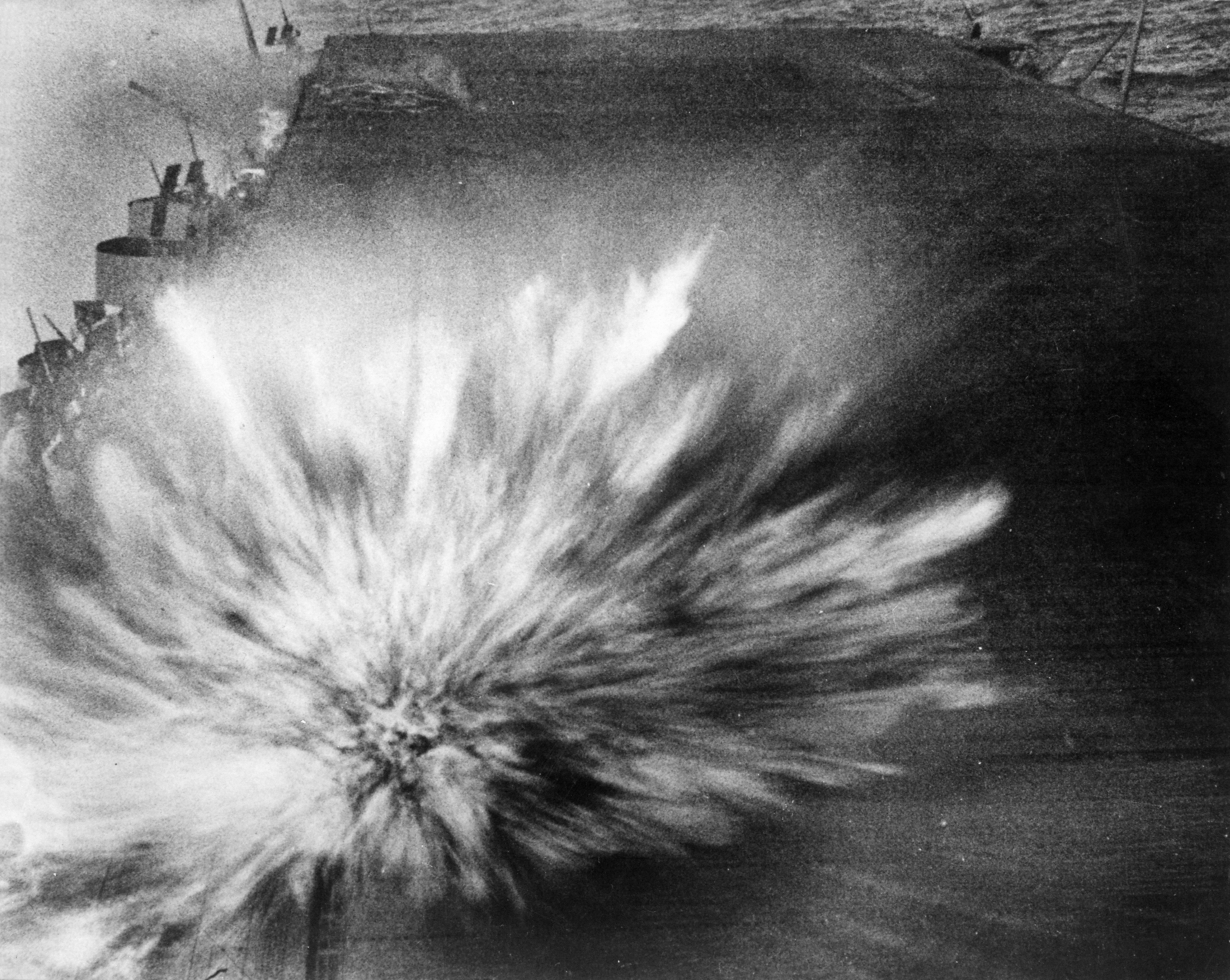

Bismarck also used her main and secondary batteries to fire at maximum depression to create giant splashes in the paths of the incoming torpedo bombers. None of the attacking aircraft were shot down. Bismarck evaded eight of the torpedoes launched at her, but the ninth struck amidships on the main armoured belt, throwing one man into a bulkhead, killing him, and injuring five others.

The explosion also caused minor damage to electrical equipment. The ship suffered more serious damage from manoeuvres to evade the torpedoes: rapid shifts in speed and course loosened collision mats, which increased the flooding from the forward shell hole and eventually forced abandonment of the port number 2 boiler room. This loss of a second boiler, combined with fuel losses and increasing bow trim, forced the ship to slow to 16 knots. Divers repaired the collision mats in the bow, after which speed increased to 20 knots.”

Prince of Wales, low on fuel but not yet forced to retreat, closed in for another gun duel with Bismarck, though neither battleship hit each other; at the same time, Bismarck’s repair teams managed to prevent seawater from entering the turbo-electric generator feedwater system, which could have been catastrophic; they also siphoned uncontaminated fuel from the forward tanks, which lightened the weight forward, allowing Bismarck to once again pick up speed.

As the chase extended into open ocean, the threat of Submarines forced the three British shadows behind Bismarck to begin Zig-Zagging, each leg of the maneuver being some ten minutes, and, in the last few minutes of the portward maneuver, Bismarck would be out of range of Suffolk’s radar.

Bismarck accelerated to maximum speed, then turned west, followed by northwards, looping back on her previous course and successfully breaking radar contact; with the shadowing forces unable to regain radar returns on Bismarck’s position, the British had, essentially, lost the battleship.

Two days later, on May 26th, Bismarck was discovered once more, less than 700 miles away from safe harbour in Occupied France. Most of the Royal Navy’s ships that had set off in pursuit, and eventually to search for Bismarck were low on fuel, out of position, or both, which left only one option for the Admiralty to try and slow or stop the battleship before she reached the protective envelope of U-boats and Luftwaffe planes.

Ark Royal.

The carrier was several hundred miles away, but her planes were less than 60 miles away from where Bismarck had been spotted by a Catalina Flying Boat; at the same time, HMS Sheffield had also been dispatched to try to get a radar lock on Bismarck, which unfortunately had not been communicated to the pilots of 818 squadron.

In the thick fog of the day, Ark Royal’s pilots dove on the first ship they saw, failing to check target; it was only due to their torpedoes being armed with new and untested magnetic detonators that Sheffield was not sunk that day; Re-arming the planes with contact detonator fitted torpedoes, the attack wave that would carry the golden bullet took off at 19:10 (7:10 PM), 9 hours after Bismarck had been spotted.

'Stringbags' launching into a Force 8 storm required spectacular timing on the parts of the pilots; if they rolled forward at the wrong moment, the plane would be swallowed by the waves crashing over Ark Royal's forward flight deck.

'Stringbags' launching into a Force 8 storm required spectacular timing on the parts of the pilots; if they rolled forward at the wrong moment, the plane would be swallowed by the waves crashing over Ark Royal's forward flight deck.

“At 20:47, the torpedo bombers began their attack descent through the clouds. As the Swordfish approached, Bismarck fired her main battery at Sheffield, straddling the cruiser with her second salvo. Shell fragments rained down on Sheffield, killing three men and wounding several others, prompting Sheffield to quickly retreat under cover of a smoke screen. The Swordfish then attacked; Bismarck turned violently as her anti-aircraft batteries engaged the bombers. One torpedo hit amidships on the port side, just below the bottom edge of the main armour belt. The force of the explosion was largely contained by the underwater protection system and the belt armour but some structural damage caused minor flooding.

The second torpedo struck Bismarck in her stern on the port side, near the port rudder shaft. The coupling on the port rudder assembly was badly damaged and the rudder became locked in a 12° turn to port. The explosion also caused much shock damage. The crew eventually managed to repair the starboard rudder but the port rudder remained jammed. With the port rudder jammed, Bismarck was now steaming in a large circle, unable to escape from Tovey's forces. Though fuel shortages had reduced the number of ships available to the British, the battleships King George V and Rodney were still available, along with the heavy cruisers Dorsetshire and Norfolk.”

“Bismarck attempted to steer by alternating the power of her three propeller shafts, which, in the prevailing force 8 wind and sea state, resulted in the ship being forced to sail towards King George V and Rodney.”

Unable to retreat, Bismarck expressed her displeasure by once again opening fire at Sheffield, straddling the cruiser with a quartet of near-misses that prompted her to once again flee; as Sheffield broke contact, she turned over the mission to maintain contact with the Bismarck to a group of five destroyers, the Tribal-class Cossack, Sikh, Maori, and Zulu, and ORP Piorun (Thunderbolt), of the Free Polish Navy.

ORP Piorun, a British-made N-class destroyer, was returned to the Royal navy after World War 2, and recommissioned as HMS Noble.

ORP Piorun, a British-made N-class destroyer, was returned to the Royal navy after World War 2, and recommissioned as HMS Noble.

“Arriving first on the scene with the British Tribal-class destroyer Maori, Piorun charged at Bismarck by herself, while Maori manoeuvred for position to fire torpedoes. Alone, Piorun exchanged fire with Bismarck for an hour, with neither side scoring any hits—although after the third salvo, Bismarck missed by only 20 yards, causing Captain Pławski to pull away. According to one report, Pławski transmitted the message "I am a Pole" before commencing fire on Bismarck; other sources say the signal to commence fire was "Trzy salwy na cześć Polski" ("Three salvoes in honour of Poland").”

Cossack also ended up facing Bismarck’s ire in the nighttime fog, a shell carrying off the destroyer’s entire radio mast, even as the five destroyers fired star shell flares and launched torpedoes, attempting to harass and exhaust Bismarck’s crew before the arrival of the main force.

“Numerous hits were reported by wishful captains and for a while the German ship lay stopped dead in the water, but continued to spit fire whenever a destroyer came too close. After an hour she got underway once more. Star shells, once fired in the steadily worsening weather illuminated the great battleship, but also revealed the destroyers in the darkness, a great help to Bismarck’s gunners.”

All five destroyers were forced to disengage between 5:00 and 7:00 in the morning of the 27th, Piorun due to very nearly running out of fuel, while the Tribal-class destroyers due to running out of ammunition.

The last of the five destroyers to break contact, Maori, stayed around until the King George V sighted Bismarck at 8:43 AM, and in fact would try to rescue survivors after the battle’s conclusion.

“Norfolk, steaming from the North, sighted Bismarck first, though in the heavy weather, mistook the German ship for Rodney; she only realized her error when the battleship did not return her identification signal. Smartly turning about and retreating to avoid being taken under fire, Norfolk maintained visual sighting, once again shadowing Bismarck; after having let the battleship slip away earlier in the mid-atlantic, it was a measure of vindication.”

“At 8:43 AM on May 27th, King George V sighted Bismarck for the first time, a visage they had been longing for and dreading these recent endless days and nights. As the Bismarck emerged from a distant rain squall, she looked to Admiral Tovey like “A thick, squat ghost of a ship coming straight towards us.”

It was Rodney, the old lady of the trio, who should have been in refit docks and not in the midst of historic battle who fired first, at 8:47. To many aboard, it felt as though the aging battleship’s hullplates would separate violently from the shock of her nine 16-inch guns.

King George V’s first salvo caused the bridge’s compass to bounce out of its mounting, smashing on the deck as the draft created by the guns tore sheafs of signal papers out into the air around the bridge. Bismarck’s first shot in return caused every bridge officer on both ships to hold their breaths; Tovey later commented “It took two hours for those shots to fall.”

The first shells landed only a few hundred metres short of the Rodney, causing more than one crewman aboard the King George to privately thank the heavens that they were not the target of the intimidating battleship.

The British ships closed the range as Norfolk added her 8-inch guns to the deluge of firepower directed at the Bismarck, while the Germans held their own; Bismarck’s third salvo straddled Rodney on both sides, shell splinters destroying the old warhorse’s anti-air gun director; The Rodney’s American Exchange officer, Lieutenant-Commander Wellings, later wrote in his personal diary that ‘If the salvo had landed a mere 20 yards further aft, our entire bridge structure would have been completely wrecked, with the captain and other key personnel killed or wounded.’

Minutes after 9 AM ticked over, Dorsetshire arrived on the scene, now adding her own firepower to besieging the Bismarck from three sides; since leaving her convoy, the cruiser had steamed 600 miles non-stop.

A witness to the final battle, Naval Historian Ludovic Kennedy, was aboard HMS Tartar, and described the engagement thus;

“In all my life, I doubt I will remember another hour so vividly as that one. It was the colour contrasts I recall most, so rare in the eternal grey of voyaging at sea. The sun appeared for the first time in days, shining through blue cracks between white, racing clouds; and the wind, painfully strong, was marbling and stippling the green water, creaming the tops of the heavy, high seas. There was the somber blackness of the Bismarck and the grey of the British ships, the orange flashes of the guns, the brown of the cordite smoke, shell splashes as tall as houses, white as shrouds.

“It was a lovely sight to begin with, wild, majestic as one of our officers called it, almost too clean for the matter at hand. It seemed strange to think that in those three battleships were five thousand men; it seemed almost irrelevant for this was a contest between ships, not men.”

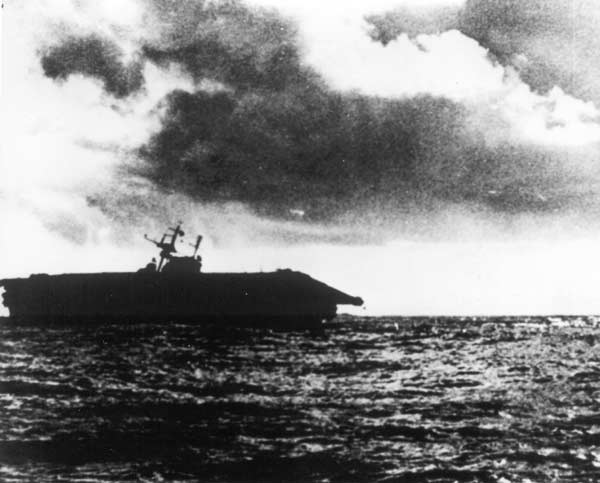

The last moments of the Bismarck, immortalized in paint. Dorsetshire lurks in the distance, waiting to pick up survivors.

The last moments of the Bismarck, immortalized in paint. Dorsetshire lurks in the distance, waiting to pick up survivors.

Bismarck’s final battle, which took from 8:47 to 10:40 that morning, could have been described as a one-sided slaughter. With Bismarck unable to steer and moving erratically, her ability to accurately aim her guns deteriorated rapidly.

“At 8:59 with the battle only twelve minutes old, a 16-inch shell from Rodney exploded between turrets Anton and Bruno, knocking both out of action. Almost at the same instant an 8-inch shell from Norfolk destroyed the foretop fire control director, taking with it Commander Adelbert Schneider and his newly-awarded Knight’s Cross. The battle had barely begun, but already Bismarck was fighting with one eye blind and one hand broken.”

Bismarck’s after turrets and director, unable to see Rodney on the port flank, instead focused on the King George V, clearly in view some two and a half miles away; with Bismarck unable to maintain a stable course, the Aft gunnery officer, Lieutenant Mullenheim-Rechberg (who would eventually be the highest-ranking survivor of the Bismarck’s crew), managed to order four salvoes before another shell, unrecorded as to its origin, would destroy the aft director, leaving Bismarck entirely blind.

It was 9:15 AM when Rodney and King George V brought their secondary guns to bear as well; while numerous hits had been scored against the Bismarck, Admiral Tovey was unsure about how much damage had been done. And so the endless hail of fire continued. One Aide to the Admiral claimed that “Shells bored their way through the armour belt like it was cheese” (A 2012 survey of the wreck would later find that only two shells, both from Rodney had penetrated Bismarck’s belt)

“Executive officer Hans Oels took command of the ship from his station at the Damage Control Central. He decided at around 09:30 to abandon and scuttle the ship to prevent Bismarck being boarded by the British, and to allow the crew to abandon ship so as to reduce casualties. Oels ordered the men below decks to abandon ship; he instructed the engine room crews to open the ship's watertight doors and to prepare scuttling charges.

Gerhard Junack, the chief engineering officer, ordered his men to set the demolition charges with a 9-minute fuse but the intercom system had broken down, so he sent a messenger to confirm the order to scuttle the ship. The messenger never returned, so Junack primed the charges and ordered his men to abandon ship. They left the engine spaces at around 10:10. Junack and his comrades heard the demolition charges detonate as they made their way up through the various levels. Oels rushed throughout the ship, ordering men to abandon their posts. On the battery deck a huge explosion killed him and about a hundred others.”

Admiral Tovey later wrote “After half an hour of action, the Bismarck was on fire in several places and virtually out of control. Only one turret remained in action, and the fire of this and her secondary armament was wild and erratic. But she still steamed on.”

The British ships continued to fire, turning the forward third of the Bismarck into a flaming ruin, gun barrels twisted skyward or drooping ‘like dead flowers’, according to one witness. At 9:21, a shell from Rodney ricocheted off of Caesar turret; the gun crew inside were unharmed, but the starboard gun would no longer elevate. Six minutes later, the mangled ruin of Turret Anton, forwardmost, fired a single salvo. Three minutes following, at 9:30, the left barrel of Turret Dora burst, shredding over 100 tons of steel like a peeled banana.

At 9:31, Bismarck fired her last salvo; then her main guns laid silent, ruined and blind. And still the British poured fire into their stricken foe. Tovey’s orders were to sink the Bismarck, to gain full revenge for the sinking of Hood, even if it meant using every ounce of ammunition available.

The expenditure was Enormous.

In all, 2,876 shells were fired at the German ship, 719 from the 14 and 16 inch guns on the two battleships.

At least 400 struck home, but, as the range was so close, the trajectory of the shells so flat that many skipped off of the waves before striking, next to no damage was done below the waterline, preventing the flooding that would have killed the battleship. At one point, Tovey, exasperated with the punishment that Bismarck was enduring, was overheard saying “Someone get my darts; we’ll see if we can’t sink her with those.”

Rodney, ordered to disengage at 10:15, fired two torpedoes from her underwater tubes at Bismarck; one hit, making it the only time in history that a battleship successfully torpedoed another battleship. As King George V and Norfolk also disengaged, the battleship and cruiser starved of fuel, Dorsetshire closed in and fired torpedoes at both sides of Bismarck as the battleship began to roll over.

At 10:40, Bismarck disappeared from the sight of men; of perhaps 400 survivors of her 2,221 crew, only 110 were picked up by Dorsetshire and the destroyer HMS Maori before both ships disengaged, having been alerted to a U-boat in the area. (As a U-boat in World War I had sunk 3 cruisers in a row as the ships were undertaking rescue operations, Admiralty policy was to leave the shipwrecked to their fates when hostile submarines were spotted)

Including survivors picked up by German ships the following day, only 114 men survived.

In-game, Bismarck is an

ungodly tough character, with the third-highest health pool in the entire fleet (beaten only by the two Ultra-rare tier Battleships), extremely respectable firepower, and an abysmal AA score that gets laughed at by some destroyers, what she brings to the table is a series of offensive and support skills built around boosting her faction members.

Firstly,

Wahrheit, or

Truth, is Bismarck’s main offense; as long as she is afloat, the first salvo of each main gun barrage always critically hits. In addition, as a reference to the noted accuracy of German rangefinding and high-velocity shells used, as long as Bismarck is using CL guns for her secondary slot, her firing range with the point-defence weapons is boosted from its default of 45-50 to 90, allowing her to snipe half the battle screen regularly, though at the expense of 35% of the secondary guns’ listed damage.

Secondly,

Unwavering Strength is Bismarck’s flagship skill. Only in effect when she is in the flagship position, it flatly boosts the damage done by all German Aircraft Carriers by 20%, and gives her at 70% chance to unload a special barrage whenever she fires her main gun.

Thirdly, and finally,

Will of the Iron Blood is Bismarck’s support skill, bumping the Critical hit rate of Main guns, Torpedoes, and Planes on all German ships in the same fleet by 20%, and boosting the reload score by 12% so everything fires just that little bit sooner. It also boosts the damage done by Tirpitz by 40%, supplanting her

Lone Queen of the North via the sisterly bond.

To the brave men and women who fought and died in war, not for ideology or profit, but for love of one's home.

While the Dorm starts with a Capacity of 2 girls, you can use gems to expand that to a maximum capacity of 6. Note that expanding the dorm does accelerate the consumption of food, so what might last your girls 24 hours with only two will only stretch for 9 and a half with a full half-dozen in place.

While the Dorm starts with a Capacity of 2 girls, you can use gems to expand that to a maximum capacity of 6. Note that expanding the dorm does accelerate the consumption of food, so what might last your girls 24 hours with only two will only stretch for 9 and a half with a full half-dozen in place. Wrangling the cats is both useful and annoying, because it’s another layer of stuff you have to sort through when you rearrange your fleets. Honestly, the big winner is Steel, who is virtually indispensable for Submarine fleets due to expanding their hunting range.

Wrangling the cats is both useful and annoying, because it’s another layer of stuff you have to sort through when you rearrange your fleets. Honestly, the big winner is Steel, who is virtually indispensable for Submarine fleets due to expanding their hunting range. Dailies count for the mission requirements of ‘get into fights’, ‘do a daily’, and so on, so just by smacking the 6 dailies that are nominally unlocked after you’ve started to beat up stuff for cognitive chips, combined with the hard mode trifecta, you’re already 90% of the way to probably the most-involved daily mission being completed.

Dailies count for the mission requirements of ‘get into fights’, ‘do a daily’, and so on, so just by smacking the 6 dailies that are nominally unlocked after you’ve started to beat up stuff for cognitive chips, combined with the hard mode trifecta, you’re already 90% of the way to probably the most-involved daily mission being completed. Nominally, Reserve Enhancement plates for Purple or Gold-tier gear, though there’s a few items worth holding onto from the blue-tier list. Specifically, fire extinguishers, unless you feel you can laugh off later-game incendiary attacks.

Nominally, Reserve Enhancement plates for Purple or Gold-tier gear, though there’s a few items worth holding onto from the blue-tier list. Specifically, fire extinguishers, unless you feel you can laugh off later-game incendiary attacks. By building a single light girl a day and clearing the dailies, you’ll actually make a profit of 30 cubes a week as a bare minimum; for the cost of one, you’ll collect a total of four daily from the missions, and the weeklies lets you accumulate another dozen.

By building a single light girl a day and clearing the dailies, you’ll actually make a profit of 30 cubes a week as a bare minimum; for the cost of one, you’ll collect a total of four daily from the missions, and the weeklies lets you accumulate another dozen. Speaking from personal experience you’ll always be short of Red Books, because attack skills are going to be your bread and butter. Most people typically suggest getting your girls’ skills up to tier 6 out of 10 because after that point it takes more than one Gold-tier skill book to level it further

Speaking from personal experience you’ll always be short of Red Books, because attack skills are going to be your bread and butter. Most people typically suggest getting your girls’ skills up to tier 6 out of 10 because after that point it takes more than one Gold-tier skill book to level it further The fuel-hungry commission will drag a level 1 girl to level 19 without a care in the world, drop a minimum of 4,500 gold on your lap, and dunk a lapful of rewards onto you; one of the more-coveted rewards is the 5-8 cube option, but gold skillbooks and tier 3 upgrade plates are also in the running.

The fuel-hungry commission will drag a level 1 girl to level 19 without a care in the world, drop a minimum of 4,500 gold on your lap, and dunk a lapful of rewards onto you; one of the more-coveted rewards is the 5-8 cube option, but gold skillbooks and tier 3 upgrade plates are also in the running. Sadly, there’s also the rare chance of 5-8 quick finishers, which is a booby prize. The game at least forewarns you of what it’ll drop on your lap, which is nice, but it will let that fuel-hog mission sit and linger until you accept it.

Sadly, there’s also the rare chance of 5-8 quick finishers, which is a booby prize. The game at least forewarns you of what it’ll drop on your lap, which is nice, but it will let that fuel-hog mission sit and linger until you accept it. In North America time, that’s 10 PM Eastern, or 7 PM Pacific for when the ‘overnight’ commissions drop. Fuel, Gold, Cubes, and Skillbooks are all potential rewards.

In North America time, that’s 10 PM Eastern, or 7 PM Pacific for when the ‘overnight’ commissions drop. Fuel, Gold, Cubes, and Skillbooks are all potential rewards. While some people will demand that you farm the fox mines until both Akagi and Kaga fall out, more-practically, it’s simply a good spot to farm experience for lower-leveled girls, with 8 fleets, an ammo restock, and a level range of 32-35 on Normal difficulty.

While some people will demand that you farm the fox mines until both Akagi and Kaga fall out, more-practically, it’s simply a good spot to farm experience for lower-leveled girls, with 8 fleets, an ammo restock, and a level range of 32-35 on Normal difficulty. Exercises, aka. Automated PvP, is encouraged, but generally a background noise timekiller than anything practical. Its main draw is that it always gives full Exp, win or lose, as well as Merit points, win or lose. Win matches and you’ll gain ranks, meaning more merit points per match.

Exercises, aka. Automated PvP, is encouraged, but generally a background noise timekiller than anything practical. Its main draw is that it always gives full Exp, win or lose, as well as Merit points, win or lose. Win matches and you’ll gain ranks, meaning more merit points per match. As a sidenote, the map selection panels will also tell you which girls you’ve collected on that map’s area if you tap the silhouette of a girl’s head; It might not tell you where to find some of the girls (Archives can do that, actually), but it will tell you what you’ve found in that area in case you want to hunt down a certain lass for limit breaking.

As a sidenote, the map selection panels will also tell you which girls you’ve collected on that map’s area if you tap the silhouette of a girl’s head; It might not tell you where to find some of the girls (Archives can do that, actually), but it will tell you what you’ve found in that area in case you want to hunt down a certain lass for limit breaking. In general, the big prizes in the Core Data shop, which is refreshed monthly, are the extended batteries and submarine snorkel, the VF-17 Fighter Squadron, and the 818 Swordfish Torpedo Bomber Squadron. The unique Battleship ammunition and the Rainbow-tier Oxygen Torpedos are also incredible auxiliary equipment.

In general, the big prizes in the Core Data shop, which is refreshed monthly, are the extended batteries and submarine snorkel, the VF-17 Fighter Squadron, and the 818 Swordfish Torpedo Bomber Squadron. The unique Battleship ammunition and the Rainbow-tier Oxygen Torpedos are also incredible auxiliary equipment. While I have spent a few dollars on AL, I’ve held off on fiscal mismanagement for this year, so I’m doing something right.

While I have spent a few dollars on AL, I’ve held off on fiscal mismanagement for this year, so I’m doing something right. Honestly, while there are a few items that are Gem-exclusive and entirely quality of life improvements, such as expanding your dock capacity (at 200 gems for 10 slots, the real money comparison is approximately $3.33 USD per Dock upgrade), the main use of Gems is for People to leer at incredibly skimpy and.or Animated character skins. Most Notably is the American Light Cruiser St. Louis, which has a barely-there dress worth 1080 gems; Approximately 18$

Honestly, while there are a few items that are Gem-exclusive and entirely quality of life improvements, such as expanding your dock capacity (at 200 gems for 10 slots, the real money comparison is approximately $3.33 USD per Dock upgrade), the main use of Gems is for People to leer at incredibly skimpy and.or Animated character skins. Most Notably is the American Light Cruiser St. Louis, which has a barely-there dress worth 1080 gems; Approximately 18$ You have a HMS Unicorn nendroid.

You have a HMS Unicorn nendroid.